CultureWorks partnered with Awakening for the fourth year in a row, providing leadership and training for the visual arts track.

Awakening is a week-long gathering for high school students to explore faith, worship, their gifts and their relationship with God, and we were delighted to be in-person this year among students full of faith, excitement, and curiosity.

Honestly, when we heard that “Rejoice” was the theme this year, we struggled with how to approach it in an appropriate way, given the backdrop of social/political unrest, spiritual division, and physical sickness. But the more we reflected we realized that the covenant we have in Christ gives it new meaning. Perhaps rejoicing is the undercurrent of a greater covenant that withstands circumstances. Maybe it’s a knowing nod towards the deeper eternal promises imbedded in the restless waters. Perhaps we can indeed rejoice if we have an Eternal Unseen, even when what we do see is scary, messy, uncertain, or broken.

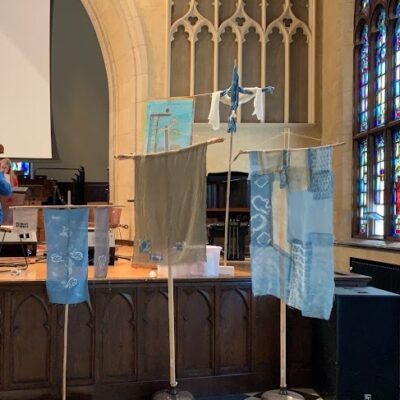

This summer, we worked with natural dyes and embroidery to talk about rejoicing as an intentional action in light of the covenant of baptism. Using indigo, Saxon blue, and pomegranate skin yellow, students died lengths of merino wool fabric. We talked about the historical and international traditions of textiles in the church: from decorative banners to garments worn in worship. Once the wool was dried and ironed, students had the opportunity to then stitch their pieces together using a variety of stitch techniques. These beautiful pieces were then displayed at the week’s final Celebration of Worship.

We also had the opportunity to share in chapel about how the visual arts and creative writing can be used in a worship setting. I read a revised short piece that I wrote a few years ago about the covenant of baptism, while Emily painted a lovely coinciding image while the piece was read. Feel free to read the full text below.

Awakening: Rejoice

By Erin Drews

My earliest memories involve water. The first thing I can ever remember is curiously placing my hand on a pancake griddle. It happened so quickly, and my mother ran my hand under ice cold water as I yelped in that distinct way a child does when a new point of pain is discovered. The second thing I can remember is the inescapable warmth of a fever and my tiny body being placed in a cold bathtub to bring my temperature down. In both instances, water soothed me; it made me better and it made me whole.

Water continued to serve as a solace for me, particularly in the form of Haltimen Pool, our neighborhood pool in Muncie, IN. In the dog days of summer, it was a mecca in its own right. Families would make the pilgrimage there, armed with the holy relics of suntan lotion and foam noodles. It was a sacred place; an aquatic temple where we went to be washed by the water. And as with all temples, there was an altar known to us pilgrims as The High Dive…a place reserved for those brave enough to serve as sacrifices lifted on high to the God of the Water.

There was a particular day in which water changed me forever. I was six years old. Wrapped in the consecrated garments of towels and cover-ups, we’d made the holy expedition as a family. Once we’d arrived, we engaged in our usual sibling cycle of rejection: me trying to follow my older brother, and my little sister trying to follow me. Mom looked over the pages of a book from a slightly reclined beach chair.

“You’re a baby,” he said. “You can’t hang out with me, Erin, because you can’t even go off The High Dive.”

“Yes I can!” I said, “Yes I CAN!”

“She can,” said my four-year-old sister, in an attempt to curry my favor.

“Shut up, Annie,” my brother and I said in unison, before my defiant voice rang out again: “I CAN.

“Then do it.” He said. “Do an eggroll off of the High Dive.”

For those of you who are unfamiliar, “An Eggroll” in Pool-speak is a particular drop from a diving board in which the diver sits on the edge of the board in a little ball before tumbling forward into the water. I’d employed this technique a million times from the regular diving board. Between that and my preconceived notion about the ever-soothing nature of H20, fear failed to present itself in the face of my brother’s challenge. In fact, I didn’t think twice. All I could think about as I climbed up that endless ladder was how my brother’s best friend would be so impressed that he’d probably ask me to marry him someday.

I remember getting to the top and standing tall. Everything looked so small, including the expressionless face of my little sister, who sat watching in her floaties with her feet dipped in the deep end. I saw my mother: asleep with her romance novel shielding her face. I couldn’t understand why my brother was laughing, or why the lifeguard looked on in horrific anticipation as I assumed position. I sat at the edge of the board, curled up, arms around my legs. I focused intently on the light blonde hairs who lived on my knees before closing my eyes. I blocked out the lifeguard whistle directed at me while I rolled forward, leaving a world of chaos and sounds. Suspended in midair, I held my little legs tight while I counted how many times I spun…one…two…thr—

My back smacked the water.

The pool swallowed me whole, and the world went quiet.

The initial contact with the water stung like crazy. Yet while submerged, it stung a little less. Those moments in the water following the plunge were both reverent and painful. I was still curled up in the fetal position, absorbing what had happened. I was slow to uncurl myself, as I realized pretty quickly that the minute I left the water I would be in pain. When I finally did, my suspicions were confirmed. My back was burning and battered. I was shocked. You see, until the moment when that water smacked my back, I had only ever experienced water as soothing. My blind bravery had stemmed from a naïve notion that water could never hurt. Water was made for healing not harming. As my tiny body climbed up the side rail to exit the pool, all of the kids were looking at me. I’d been changed. It was like this new knowledge of the blurred nature of water had somehow opened my eyes to a deeper reality.

Whenever I see baptisms at church, part of me screams, “Heck Yeah, Hallelujah!” The other part of me, a six-year-old with a water-scarred back, wants to scream “ARE YOU SURE YOU KNOW WHAT YOU’RE DOING?” To be baptized is to die and resurrect with Christ. It’s an active covenant, the water serving as a visible sign of an invisible grace. But do you know what that grace entails? It requires an utter death to self, and along with it the things you hold too tightly in exchange for your hands to be filled again by One with greater foresight. That water signifies a deep promise of protection, abundant love, and eternal life, but it’s also a guarantee for instances in this life that require your complete and utter submission for purposes far greater than you can ever understand. And when that cannot happen by your own accord, this God of the water-covenant will take you kicking and screaming away from that which you need to let die, and hold you in his care while you become new.

Baptism has obvious implications: that we will be resurrected with Christ and dwell among him forever in our eternal glory in the redeemed Creation. All that jazz. But whether we’re letting a priest gently anoint our babies’ heads or going down to The River in herds, I don’t think we consider the many mini-deaths and resurrections that this covenant ensures in this life. It’s a covenant that requires constant loss and renewal, and we are promised the grief just as clearly as we are promised the grace. If we knew that, would we still throw pizza parties afterwards? Would we dress our babies in Osh Kosh and invite our families to the affair? I think if we really knew, we’d pray for protection over the subject receiving that water; we’d adorn ourselves in sackcloths and ashes; we’d discuss spiritual insurance policies while Aunt Linda cuts the cake.

This begs the question: whether the water heals or harms, how do we rejoice? We’ve been focusing on the verse from 1 Thessalonians: Rejoice always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus.” I don’t know about you, but sometimes I don’t know what to do with that. In the wake of grief, rejoice? In the face of incurable cancer, rejoice? Up against seemingly insurmountable systemic injustice, rejoice? What does it mean? Well, the word rejoice comes from the Old French “rejoiss” in the 13th century, meaning “to own, possess, enjoy the possession of, have the fruition of [joy].” You see, rejoicing is something you possess, given to you through grace. You carry it with you; you don’t contrive it lightly, but rather prayerfully cling to it. And no matter the waters we’re led through- painful or healing- we’ve been washed by the One who bestows upon us “rejoicing” for our own possession. Rejoicing is the undercurrent of the greater covenant that withstands all circumstances; the deeper eternal promises imbedded in both the healing and restless waters. So while I love our verse from Thessalonians, I want to shift our attention to a good word from 2 Corinthians 4:16-18

16 Therefore we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, inwardly we are being renewed day by day. 17 For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. 18 So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.

That fateful day, as I plummeted off of the High Dive and into the water, I walked away changed. I learned that swimming can be both terrible and glorious at the same time. Yet it didn’t alter my perception of water enough to prevent me from returning to the pool.

Fix your eyes, my friends, upon the Lord who is capable of giving more than we can ask or imagine. May we adjust our expectations this side of eternity, not as a means of defeat but rather a path towards joyful surrender knowing full well that we serve a good God who will exceed them.

In fact, he already has. By taking on flesh to wade in the water with us, he already has.

And that is cause for rejoicing.